Traffic Light

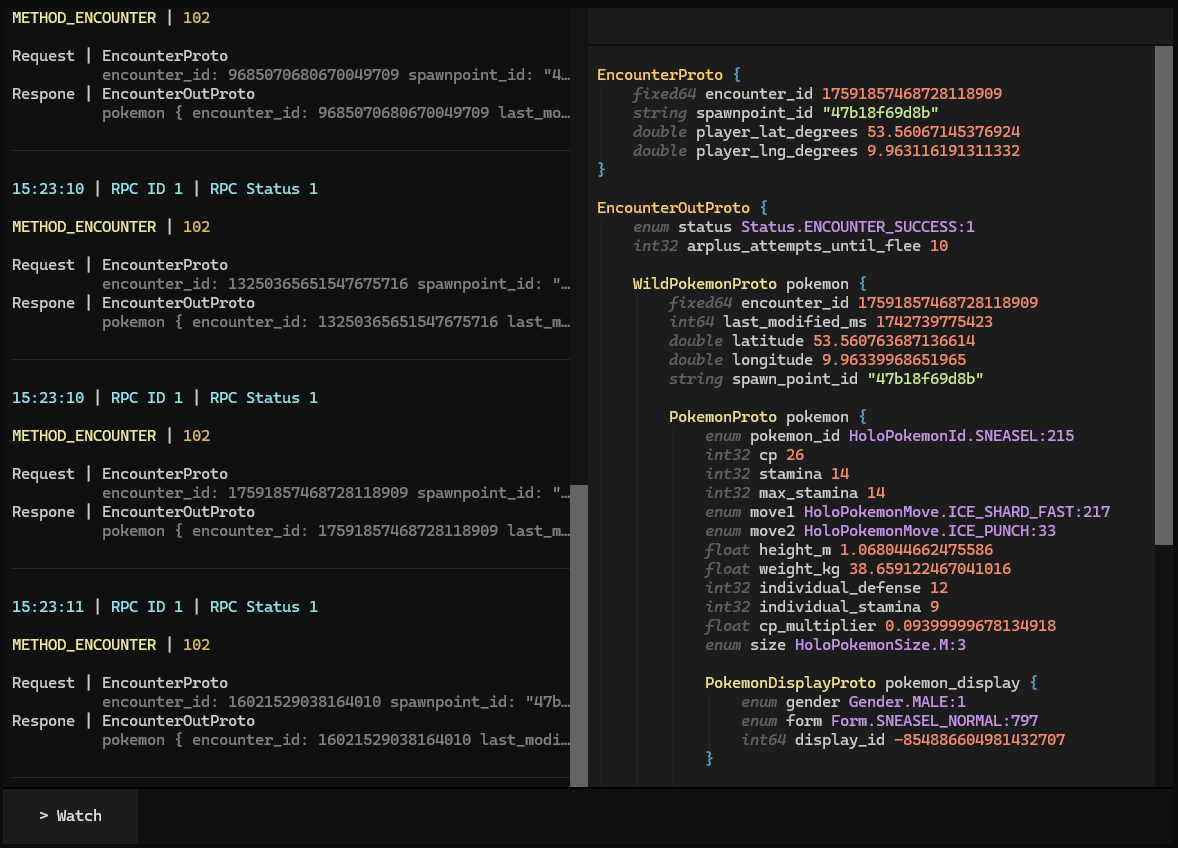

Traffic Light is a specialized network logger designed for Pokémon GO. It’s an essential tool that enabled a lot of modern advancements within the mapping ecosphere.

How to encounter a Sneasel

Pokémon GO relies on Google’s protobuf protocol for its network communication. Each request is sent with a method enum and request data and gets back response data. This protocol ensures type-safe interactions between the game client and server. Data is structured into messages, serialized into compact byte arrays for efficient transfer, and then deserialized back into usable data on the receiving end. Each request made by the game includes a method identifier and a protobuf message.

Let’s look at how an encounter with a wild Sneasel works under the hood. First, we need to find the correct method ID and request structure. We can get that by observing the traffic with Traffic Light, or by directly searching the protobuf definitions.

For encountering, the relevant method is METHOD_ENCOUNTER = 102 and the corresponding structure looks like this:

message EncounterProto {

fixed64 encounter_id = 1;

string spawnpoint_id = 2;

double player_lat_degrees = 3;

double player_lng_degrees = 4;

}To start the encounter, we need to populate this structure with the appropriate values. We get these from another request that we sent beforehand.

>>> request = EncounterProto()

>>> request.encounter_id = 17591857468728118909

>>> request.spawnpoint_id = "47b18f69d8b"

>>> request.player_lat_degrees = 53.56067145376924

>>> request.player_lng_degrees = 9.963116191311332Next, let’s serialize this request to a byte array that we can send to the game servers. (How exactly is way beyond the scope of this article)

>>> request.SerializeToString()

b'\t}\x8e\xd7\x82)\xd5"\xf4\x12\x0b47b18f69d8b\x19\xad\xde\n\x15\xc4\xc7J@!J\xdc\xbf\x90\x1d\xed#@'We get a long byte array back that we can now plug into EncounterOutProto, the structure for the response data. And that’s our Sneasel! It’s shiny with 26 CP and individual values of 0/12/9.

EncounterOutProto {

status ENCOUNTER_SUCCESS

pokemon {

encounter_id 17591857468728118909

last_modified_ms 1742739775423

latitude 53.560763687136614

longitude 9.96339968651965

spawn_point_id "47b18f69d8b"

pokemon {

pokemon_id SNEASEL

cp 26

stamina 14

max_stamina 14

move1 ICE_SHARD_FAST

move2 ICE_PUNCH

height_m 1.068044662475586

weight_kg 38.659122467041016

individual_defense 12

individual_stamina 9

cp_multiplier 0.09399999678134918

size M

pokemon_display {

gender MALE

shiny true

form SNEASEL_NORMAL

display_id -854886604981432707

}

}

}

...

}While this example is quite straight-forward, with over 500 methods in the game you can’t just guess how these requests are supposed to look like!

Building Traffic Light

Around 2021, we reached a point where it became feasible to send arbitrary network requests, like the above Sneasel encounter. However, finding what data goes where was largely a process of trial and error.

This lead to the creation of Traffic Light. It was designed to beautifully visualize the game’s network traffic, making it easier to understand and replicate requests within our tools. Third-party MITM tools intercept the game traffic and send the raw data to a HTTP endpoint set up by Traffic Light.

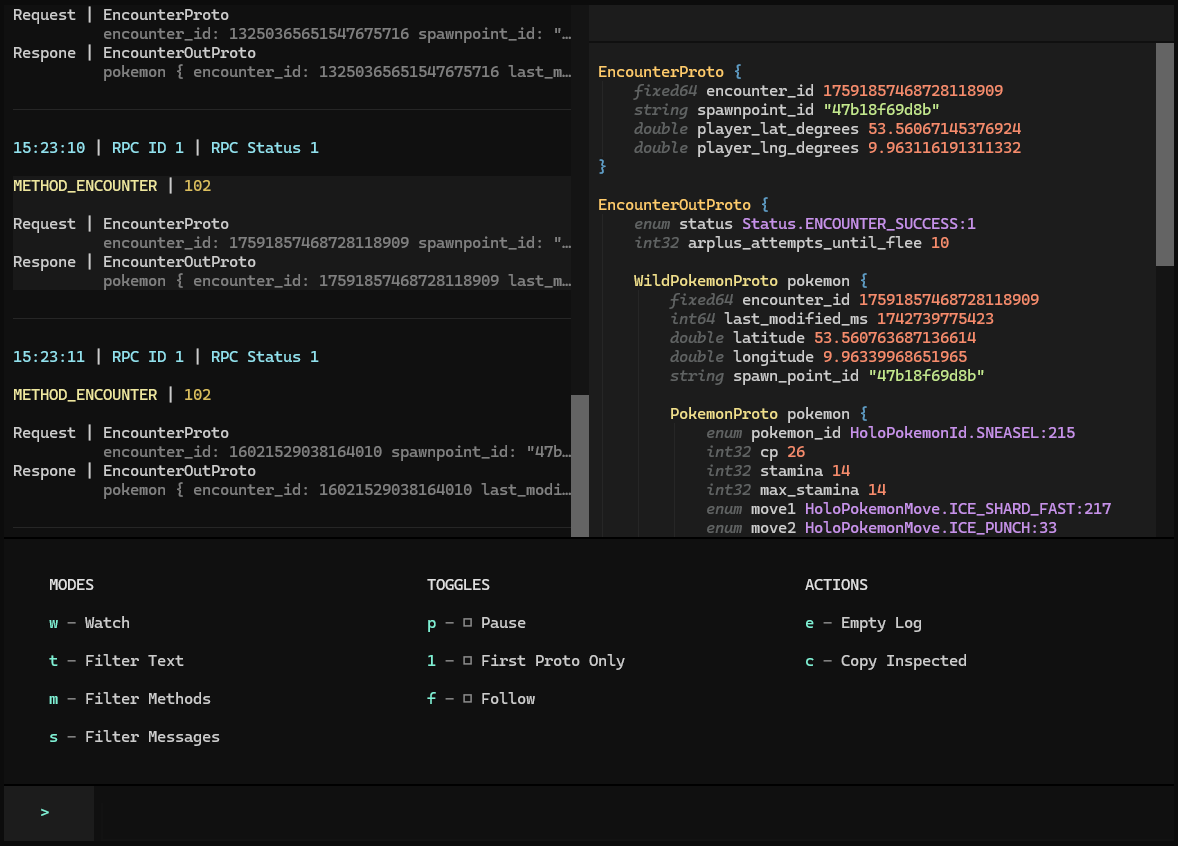

After coming across Textual, a nice python library for creating terminal-based user interfaces, I chose to build Traffic Light as a terminal application. At the time, Textual was undergoing significant development changes and offered little documentation, limiting me to mainly referring to available source code while implementing the UI.

Note-worthy features include custom styling and syntax highlighting of the protobuf data, tailored to our specific needs. And a bunch of quick actions, allowing to interact with the data stream and inspected data.

Traffic Light significantly improved our understanding of Pokémon GO’s inner workings, enabling faster implementation of new features and the discovery of several major game exploits.

Looking back, the biggest pitfall with this project was deciding to make it a Terminal UI. Although it was fun and a great learning experience, the UI does feel very limited in its interactivity and can get really sluggish with a lot of requests in its backlog. Regardless, I’m happy with how it turned out and the doors it opened for us.